We may earn money or products from the companies mentioned in this post.

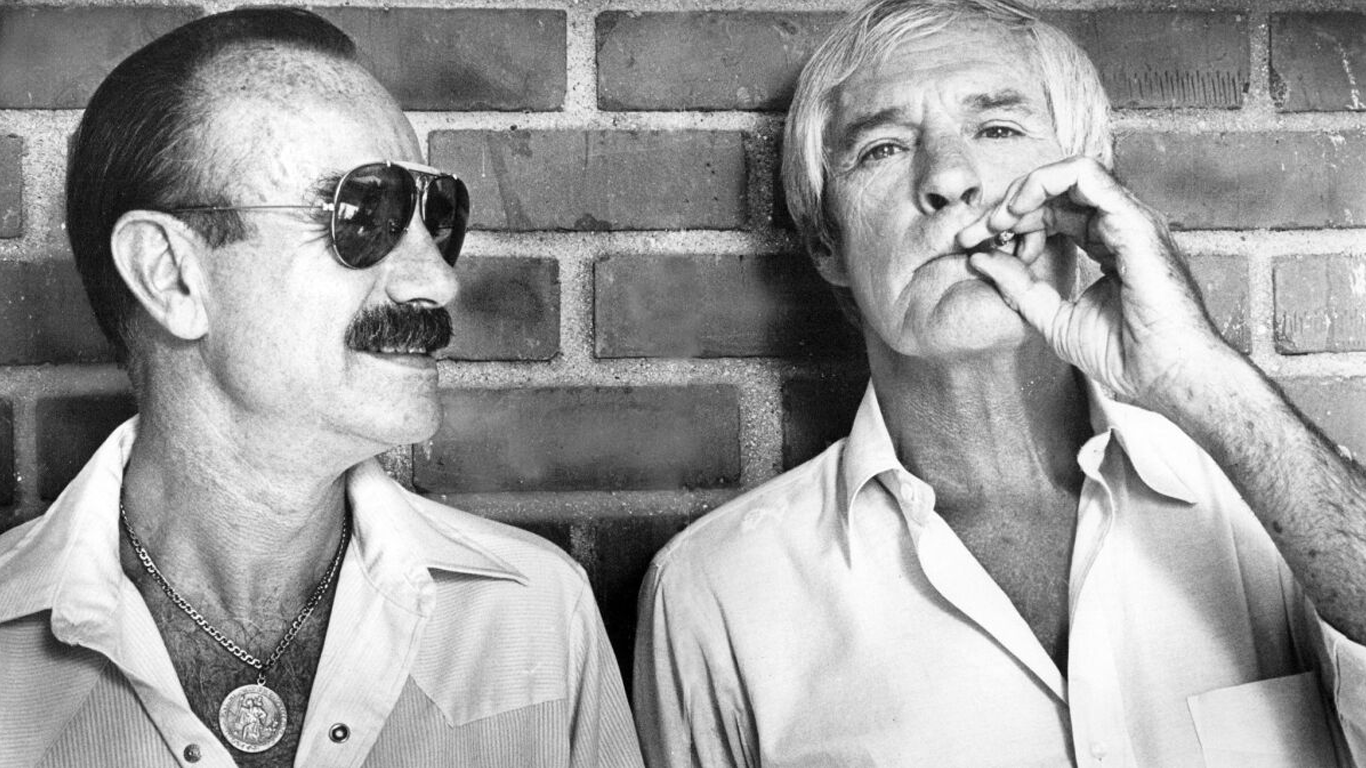

Last week, I applied Timothy Leary’s definition of a “game” to role-playing and ended with a promise to discuss other passages in his presentation “How To Change Behavior” that, despite having nothing to do with role-playing, are strangely applicable to our hobby. Here’s the first passage I was talking about:

“All behavior involves games. But only that rare Westerner we call ‘mystic’ or who has had a visionary experience of some sort sees clearly the game structure of behavior. Most of the rest of us spend our time struggling with roles and rules and goals and concepts of games which are implicit and confusedly not seen as games, trying to apply the roles and rules and rituals of one game to the other games.”

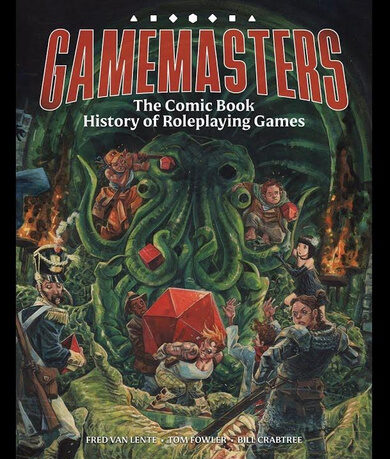

While this could certainly apply to clashes of gaming style or theme (you don’t play TOON the same way you’d play Call of Cthulhu), the thing I see more often is gamers trying to apply the “roles and rules and rituals” or role-playing to the social interaction “game.” When a GM or player posts on Reddit or asks a question at one of our convention panels about problem players, it’s not unusual for (non-Hex) people to suggest using the game rules or setting conventions to “teach them a lesson.” Unfortunately, object lessons rarely work. Which brings us to the next Leary quote:

“But this old game should be made explicit if it is to be fun. Unfortunately, the West has no concepts for thinking and talking about this basic dialogue. There is no ritual for mystical experience for the mindless vision. What should provoke intense and cheerful competition too often evokes suspicion, anger, and impatience.”

If you replace the sentence about mystical experience with “There is no ritual for discussing disagreements,” you end up defining one of the core problems that afflicts many gaming groups. RPGs don’t have a ritual for talking openly about problems, possibly because of confrontation-averse geek social fallacies that come into play during this particular variant of the social interaction game. Saying “I don’t like this” or “there’s a problem here” simply doesn’t occur to a lot of gamers because it’s seen as exclusionary or bullying.

Fortunately, Leary provides a perfect solution for preventing many of these problems, and with them the possibility of scary/ostracizing confrontations, right from the outset:

“In our research endeavors, we have developed eleven egalitarian principles based on the game nature of the human contract equality in determining role, rule, ritual, goal, language, commitment; equality in the explicit contractual definition of the real, the good, the true, the logical; equality of the right to speak and to have access to relevant information. Any contract between men should be explicit about any temporary suspension of these equalities.”

This is pretty much a description of your basic social contract for a gaming group, which some groups can assume and others really need to talk about before the game begins. In the case of RPGs, the most important portion of the creating the contract is probably being “explicit about any temporary suspension of these equalities,” since in many cases these equalities will be suspended in favor of GM control during the game. A common problem in games is that these equalities are suspended before the game ever starts, with the GM assuming a level of control from the beginning that makes players feel like they don’t have a say (or have less of a say than the GM) about how the game will be played. While most games require that GMs have an unequal level of control over the game, it’s important that the control is given to the GM by the players, not simply taken by virtue of the fact that she’s agreed to run the game. With that in mind, let’s unpack Leary’s 11 principles as they relate to gaming.

1. Role

While most games come down to a GM and players, there’s a lot of variation as to how much players are permitted to contribute to the world and the story. Is it ok for the players to fill in details about the world relating to their characters’ backgrounds? Pursue player-generated character subplots? Make up legends or rumors that their characters have heard and the GM can use as a basis for adventures? Create setting elements that have nothing to do with their characters?

2. Rule

What system you’re using is obviously the major concern here, but it’s also important that everyone gets to weigh in about which optional rules to use, what rules are going to be ignored or changed, and whether any additional house rules are necessary.

3. Ritual

This is all the stuff surrounding the actual playing of the game: start and end times, rules relating to the use of mobile devices at the table, whether the group will order pizza, etc. Some game aspects, like whether the group will use miniatures or other non-essential but helpful accessories, may also be included here.

4. Goal

The goal of the game is mainly about the balance between rules and storytelling. In some cases, it might include in-game goals, like whether the PCs will be working for a particular faction or trying to overthrow it.

5. Language

Since (outside of online games, at least) it’s usually a safe bet that all players speak the same language, I’d put discussion of things like genre and tone here and define language as the set of character archetypes, tropes, and other story elements that will be common to the game. The last time I played D&D regularly, for instance, the language was essentially Tolkienesque, but later versions seemed to have more of a “Star Wars Cantina” language that includes lots of weird character races and classes that make even less sense together than the classic D&D party.

6. Commitment

The biggest commitments involved in most RPGs is time, so this is where everybody decides things like how long the group will wait for players who are running late, how early the host is ok with people showing up, and how to deal with players who are consistently late or absent. Material commitments, like rulebooks or game components players are expected to bring or systems of determining who’s responsible for bringing snacks and beer, should also be discussed here. You’ll also want to decide how much players are expected to contribute to the story. Will the characters be reactive or pro-active? Can players who pursue player-generated character plots and help flesh out the world expect to play a larger role in the story?

7. The Real

For games, this will usually involve setting information, especially when you’re using a published setting with variations. If players are allowed to introduce setting elements, you’ll also want to set any rules for how setting elements are introduced. For example, if it’s a “monsters don’t exist but they really do” setting where the characters start as people who don’t know the truth, players who want to introduce monsters or magic may be required to frame these things as second-hand knowledge, not personal experience.

8. The Good

Since in part one, “good” was defined as one of the determiners of value, I think this is a good place for setting expectations for player behavior and the desired overall “feel” of the game. How well is everyone expected to know the mechanics? How is is meta-gaming defined and when (if at all) is it permitted? Do we have to go through that elaborate charade of pretending to accidentally discover that we should use fire to kill the green slime, or can we make a knowledge roll or assume our characters have heard about it from the thousands of other adventurers hanging out in the local tavern? How much agency do players have in determining story goals and character destinies? What works of fiction are we using as models?

9. The True

Since the GM is the players’ primary link to the fictional world, it’s important to establish when the GM can and cannot be trusted. Can information that the GM gives the players through an in-game source such as a dusty old book or NPC be presumed accurate, or should the players assume that such information is often based on limited information, incorrect assumptions, and personal or cultural biases? What about information gained from knowledge checks or similar game mechanics? Is such information The Truth or just what the character has been taught is true?

Truth is another case where the balance between game rules and storytelling comes into play. Do the players expect the GM to always follow published game rules as written, or is he allowed to tweak things like monster abilities to make for a better story? There should also be discussion of when the game rules should be ignored in favor of story (many groups have a “nobody dies because of a random die roll” rule, for example). It should be noted that, with the exception of those who take pleasure in TPKs, most GMs fudge rolls in the players’ favor a lot more than the players realize, so this is more a matter of how blatantly the GM is allowed to cheat than whether he’s allowed to fudge the occasional roll. If the group is part of the “let the dice fall where they may” crowd, the GM will need to pretend that everything was done by the book rather than admitting that he cut the bad guy’s hit points in half because the fight was getting boring or the whole party was about to die.

10. The Logical

For RPGs, I think logic would equate to genre rules and the interplay between realism and drama. The logical solution to a problem for an action movie cop is rarely the logical solution to the same problem for a cop in the real world. This is where you decide whether genre conventions or realism is more important for the game you want to play.

11. Right to Speak and Have Access to Relevant Information

For gaming, this almost needs to be broken down into two separate items. For the first half, everyone should always have a right to speak up about that game, but most groups don’t want complaints or rules arguments to bog down the game. “The GM makes a ruling and we can discuss it later” is a fairly common agreement here.

As for “Access to Relevant Information,” there are probably two RPG situations where this comes into play. The first is when the character would know something that the player doesn’t. If that’s the case, the GM should provide the player with the information. I’ve seen a lot of GMs let a game bog down or allow the players to make a bad decision because the players didn’t know something that their characters could be expected to know. Don’t do that.

The other situation where relevant information comes into play is trickier because it involves the players’ basic assumptions about the game world. Some players are perfectly fine when their characters run into weird stuff in Deadlands (since they know it’s going to happen), but would feel betrayed if their Cyberpunk characters were attacked by a werewolf. Other players are just the opposite and enjoy when the game takes a turn they never expected. Unfortunately, it’s hard to discuss these sorts of twists without letting the cat out of the bag. GMs who plan to make major changes to the status quo of the game world need to either know their players’ preferences going in or introduce those changes in a subtle enough way that they can be explained away or reversed if the players don’t seem to like where the game is going.

A lot of gaming groups, especially those where the players all have similar goals and play styles, can fall into this kind of gaming contract without ever explicitly discussing in, and some groups are able to work out the details as problems arise without anyone feeling that their equality is being ignored. If your group often runs into problems, though, it’s probably a good idea to set aside the first session of any new game to discuss Leary’s egalitarian principles as they apply to the game you’re starting. They won’t prevent all problems, but they should reduce the frequency of major disagreements. When those disagreements happen, remember that interpersonal relationships are not a role-playing game, so you need to use the “talk about it like grown-ups” game to resolve them.