We may earn money or products from the companies mentioned in this post.

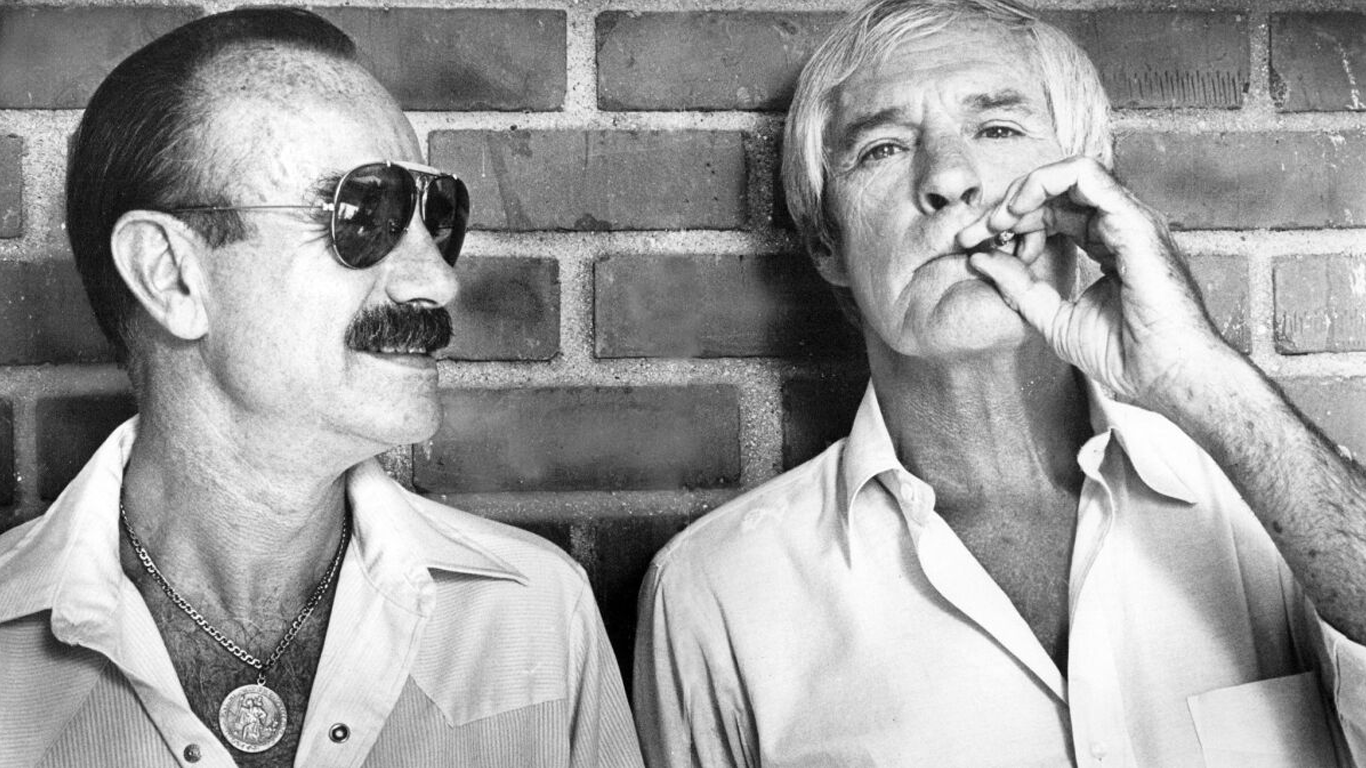

This article, which reprints Timothy Leary’s International Congress of Applied Psychology presentation, “How To Change Behavior,” recently showed up in my newsfeed. What does Timothy Leary have to do with gaming? Well, in the case of “How To Change Behavior,” the whole presentation starts with the idea of looking at behavioral sequences as games:

“The use of the word ‘game’ in this sweeping context is likely to misunderstood. The listener may think I refer to play as opposed to the stern, real-life, serious activities of man. But as you shall see I consider the latter as a ‘game.’”

In order to illustrate this assertion, Leary goes on to define what he means by “game.” Since role-playing games weren’t around when Leary gave the presentation (in 1964), I thought it might be fun to see how well his definition applies to RPGs. Leary defines a game has having six distinct characteristics:

“1. Roles: The game assigns roles to the human beings involved.”

That seems easy enough—after all, we’re talking about ROLE-playing games–but I’m not sure that Throg the Slaughterer and Thesaurus the Verbose are really what Leary had in mind. I guess it depends on whether “shoe” and “iron” would be considered distinct roles in Monopoly. Even if we ignore characters, though, RPGs still have roles, even if it’s just “player” and “GM.” Most games have additional roles: rules lawyer, munchkin, comic relief, strategist, etc., etc. So far, so good.

“2. Rules: A game sets up a set of rules which holds only during the game sequence.”

Two for two. The first part is what keeps most game companies in business. The second part is true for everyone except for fictional characters in Jack Chick tracts and cheesy made-for-TV movies starring a young Tom Hanks.

“3. Goals: Every game has its goal or purpose. The goals of baseball are to score more runs than the opponents. The goals of the game of psychology are more complex and less explicit but they exist.”

Since Leary seems to be defining goals here as what gamers might call “victory conditions” rather than reasons for playing, I’m not sure if “fun” qualifies, so the goals of role-playing, like the goals of psychology, “are more complex and less explicit but they exist.” The vagueness and fluidity of goals in RPGs can be a source of friction, especially when players don’t agree on what the goals are. Is the goal to play a character believably? To tell a good story? To overcome obstacles through “rules mastery?” To kill things and take their shit?

“4. Rituals: Each game has its conventional behavior pattern not related to the goals or rules but yet quite necessary to comfort and continuance.”

At first it might seem iffy whether this applies to RPGs. Sure, certain groups and individual players have these–pre-game rituals, weird dice superstitions, quoting Monty Python for no good reason–but do RPGs have any universal rituals? There’s at least one: the game itself; Not the rules so much as the idea of framing collective storytelling as a game with rules. Without the “game” frame, role-playing is really just playing make-believe, which is something that we learned early on was only acceptable up to a certain age. A game, on the other hand, especially a complex one, is something that adults can play without shame. I suspect the stigma against adults “playing pretend” is why some gamers gravitate towards rules-heavy systems and are sometimes uncomfortable with more free-form games like Fiasco. Having rules that no child could understand helps them justify role-playing as an adult activity somehow.

“5. Language: Each game has its jargon. Unrelated to the rules and goals and yet necessary to learn and use.”

NPC, GM, OOC, Munchkin, TPK, Bennies, and lots more. Yeah, I think we’ve got this one covered.

“6. Values: Each game has its standards of excellence or goodness.”

The standards for a good game can be very subjective depending on a particular player’s goals and preferences, but there are objective standards. Except for a few fanatics, most gamers can recognize when a game does something well or badly, even if it’s their favorite game doing something badly or a game they’d never play themselves doing something well. Games can also be recognized for excellence through popularity, sales, awards, and good reviews. At the very least, we can all agree that F.A.T.A.L. is awful, so RPGs fit qualify for this part of Leary’s definition even if our only standard is “not F.A.T.A.L.”

The rest of “How to Change Behavior” is mainly about the fact that Westerners don’t see the game element of behavior because we lack a tradition of visionary experiences, and how we should solve that with LSD and other consciousness-expanding drugs. Oddly enough, though, there are a couple of other passages in the article that are applicable to role-playing. I’ll talk about them next week.