We may earn money or products from the companies mentioned in this post.

An Interview with Sharktoberfest Writer Steve Johnson, Conducted by Dale Ryan

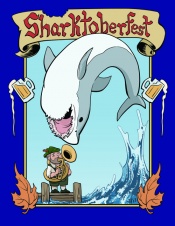

Just in time for October, Hex Games has released Sharktoberfest, written by Steve Johnson and illustrated by James and Lindsay Hornsby. I’d never really given much thought to shark movies before, but reading the book I was struck by how much time Steve has clearly put into analyzing the genre. I wanted to know more about this project came together, and Steve was gracious enough to answer my questions.

1. Sharktoberfest is an adaptable adventure that allows players to recreate the thrills of a shark movie. Why shark movies? What makes the genre compelling?

Steve Johnson: Shark movies can be compelling in a lot of different ways, but I think Quint’s line from JAWS about a shark’s “lifeless eyes, black eyes, like a doll’s eyes” is the thing that separates shark movies from other monster-type movies about real animals. Most of the other familiar big, scary critters in the real world are mammals, so even though they’re terrifying, we kind of understand them because they’ve got the same basic instincts and biological drives and in some cases even mannerisms that we do. If a lion attacks someone in a movie, there’s a sense of emotion and purpose behind it–it’s scared or hungry or protecting its territory. Sharks are completely alien to us, so they’re easy to portray as cold, emotionless killers who live to cause senseless destruction.

In addition to the shark itself, going out on the water means putting yourself at the mercy of some wood, metal, or fiberglass and a means of locomotion. If any of a thousand little things goes wrong, you can end up stuck in an environment where man is simply not equipped to survive. Even if you’ve got a way to call for help, there are plenty of things that can keep it from arriving in time. The fact that the ocean is one of the few places on earth where people can find themselves completely isolated from the modern world may be part of the reason why shark movies have made kind of a comeback in the last decade or so while other horror movies have tried to deal with how easily modern technology can short-circuit basic genre conventions.

2. Can you clarify for us what you mean by “adaptable adventure”? Is Sharktoberfest something that a gaming group could play more than once?

SJ: I think we first used the phrase “adaptable adventure” for Fratboys Vs., but Roller Girls Vs. and IMP also fall into the same basic format. We’ve also informally called them “plug and play adventures.” The basic idea is that the book is similar to a traditional RPG adventure, but with one major element left undefined. We then provide several examples of things that the GM can use to fill in the blank, along with tips for using that particular element, notes about how it may affect the default plot, game stats, and other useful stuff. The format allows more replayability than most adventures, since each game will play out quite a bit differently depending on what “plug-in” the GM uses. The format works really well with the B-movie genre, since it’s easy to look at a series of games as a string of sequels. There’s a common theme and some recurring elements, but (hopefully) enough differences to keep things interesting.

3. How much credit would you say James and Lindsay Hornsby, America’s favorite artistic married couple, deserve for this book’s existence? How much did they contribute, beyond the amazing artwork?

SJ: I think the first half-serious/half-joking discussion of doing a shark game happened in James and Lindsay’s room at DieCon, and the fact that they both seemed really excited about the idea of drawing sharks was a big factor in moving the concept from silly idea to actual product, in part because I really wanted to see their shark pictures. When it came time to actually do the art, I sent them my list of “sharkbominations.” I marked the ones I thought I wanted to include (along with a couple I knew would be included), but told them to let me know which ones they were most interested in drawing even if they weren’t marked. Since we were putting the book together pretty fast, I had most of the finished drawings (or at least sketches) by the time I started writing the descriptions, so in addition to helping me decide which sharkbominations to detail, in some cases the art helped me flesh out the scenarios or figure out how the sharkbominations worked. James also played in the first Sharktoberfest game I ever ran.

4. How much research did you do for this book? Did you learn anything that surprised you?

SJ: In addition to actually watching Shark Week on the Discovery channel, I watched every shark movie I could find. Since I live in the boonies and don’t have a fast enough internet connection for NetFlix, the success of Sharknado was really fortunate because it gave the ScyFy channel a reason to play a lot of cheesy shark movies over the next few weeks. I did a tiny bit of actual research on sharks, but not very much because this game isn’t about real sharks, it’s about movie sharks.

As for learning surprising things, towards the end of writing the book, I picked up a copy of JAWS and played it for background noise while I was working. After the movie was over, I watched the “making of” feature and was surprised to find out some of the details about the film’s production. Because of something with one of the Hollywood unions, they had to start filming before they’d finished the script, so a lot of the movie was being written and rewritten as they were filming it. Quint’s Indianapolis speech, for example, went through something like four different drafts, with Robert Shaw (the actor who played Quint) writing the final version. They also ran into all sorts of other production problems, ran over budget, couldn’t get the shark to work, and at one point Spielberg had to use his own money to reshoot a scene (in somebody’s swimming pool) because Universal refused to sink any more money into the movie. So basically the Casablanca of shark movies was filmed like we imagine all the other shark movies being made.

5. We often spend months developing, writing, and revising games. Hobomancer took about two years to complete. Sharktoberfest, on the other hand, was written in a much shorter time frame—as I recall, you were inspired by the SyFy movie Sharknado, which aired on July 11th, and the finished book came out on September 23rd. That’s a remarkably fast turnaround time for a 40 page book. Do you feel like writing, revising, art directing, and laying out the book at a white-hot speed got you closer to the experience of working on a made-for-cable shark movie?

SJ: As I mentioned earlier, there was some discussion of a shark game at DieCon back in June, but even that came out of a conversion about Sharknado, which most of us had heard about right before the con. When the movie actually aired, I sort of liveblogged about it on Facebook and pretty early on the idea of the “sharks mixed with stuff” game came up, still mostly as a joke. Between the positive reaction to the idea and my genuine enjoyment of Sharknado, I knew by the time the movie ended that I was going to write the game. I also had a rough outline, a page full of notes, and the Sharktoberfest title.

Even after I’d decided to do the book, I didn’t plan on writing it immediately, but I got a little obsessed with shark movies and kept thinking about it and making notes. Also, Sharknado was a huge hit, so we decided to strike while the iron was hot. Besides, the book is called Sharktoberfest, so it makes sense to release it in time for October. Somewhere along the line I decided we should try to get the book finished in time to have the print version on sale at Archon, so the timeline got even shorter.

Even though we finished the book really quickly, I don’t think we really put fewer hours into it than we have other books of similar size with longer production times. As we often point out, Hex is a part-time company, so normally I can only write a few hours a day because of my other job. Since I temporarily became a “man of leisure” (as Rupert Giles puts it) in August, I was able to dedicate a lot more time each day to working on Sharktoberfest, which is why I was able to finish the book so quickly. But back to the original question, working on the book nearly all the time for a few weeks was definitely a different experience than writing a few hours a day for several months and at some points there was a combination of focus, exhaustion, and “why the hell not?” that I suspect is something like making a crappy shark movie. Or, apparently, JAWS.

6. As a side note, I looked up Sharknado on Rotten Tomatoes, and it has a positive rating of 85% among critics and 41% among audiences. It’s more critically acclaimed than it is popular? How can that possibly be?

SJ: The low audience rating kind of surprises me, but I think the the high critic rating indicates that Rotten Tomatoes bases its ratings on the reviews of critics who know what they’re doing. One of the things that I think made Roger Ebert so good at his job was his ability to review every film for what it was, not in comparison to other films. Sharknado isn’t JAWS, but it’s not trying to be, so trying to compare the two is missing the point. In my opinion, Sharknado is very close to the exact movie the filmmakers set out to make. Normally when you watch a cheesy movie, you feel kind of embarrassed for everyone involved. With Sharknado you’re laughing with them, not at them. They knew what they were doing, they did it well, and it looks like they had a good time doing it. Right in the title, they tell you, “We know that the premise of this movie is completely ridiculous, but if you’ll buy it, you’re going to have a lot of fun.” Given some of the games I’ve worked on, I can appreciate that.

7. Out of the eight sample scenarios in the book, which one do you think would make the best movie?

SJ: It depends on how you define “best.” For a knowingly dumb but fun movie like Sharknado, the Sharkcano scenario is the obvious choice, but it’s a little too blatantly derivative. Instead, I’d probably go with Sharkmaggedon, if only to see a special effects version of James’s “shark Jesus” illustration. The one I’d most like to see as an unintentionally bad movie is The Sharktagon, since you can heap all sorts of crime movie cliches right on top of the shark cliches. Throw somebody like Nicolas Cage in there as the undercover Fish & Wildlife agent who plays by his own rules and you’ve got yourself a masterpiece. If you wanted to make a movie that was actually good in the traditional sense based on one of the scenarios, you’d be mostly limited to comedy, though I’d love to see what Terry Gilliam could do with the Unishark idea.