We may earn money or products from the companies mentioned in this post.

Once you’ve got an idea of the basic premise of the game and who the characters are going to be, it’s time to start figuring out what kind of world we’re going to need to accommodate them. As those of you who have bought just about any Hex supplement ever know, we like to call this world a “ficton.” I’ll just take the definition from QAGS 2E: “‘Ficton’ is a term coined by science fiction author Robert Heinlein. It means ‘fictional universe.’ Fritz Leiber’s Nehwon, Frank Miller’s Sin City, and Kevin Smith’s View-Askewniverse are all examples of fictons. A story’s ficton combines genre conventions and setting details to create a set of “rules” that governs the environment and probabilities of a story. The ficton describes what sorts of things are (and are not) allowed to happen or exist within the story. Stories can have the same world and genre without having the same ficton. For example, both Scream and Nightmare on Elm Street are slasher-type horror movies with a modern-day America setting, but they exist in completely different fictional universes. The main divergence is that the Nightmare ficton includes blatantly supernatural elements not found in the Scream ficton.”

[For those of you playing the Hex Games drinking game, that’s 1 drink for shameless self-promotion, 1 drink for defining “ficton,” and one drink each for references to Fafhrd & the Gray Mouser, Kevin Smith movies, and Wes Craven, plus a bonus drink for specifically mentioning Scream. Whether or not you want to count Sin City as a Robert Rodriguez reference is between you and your liver.]

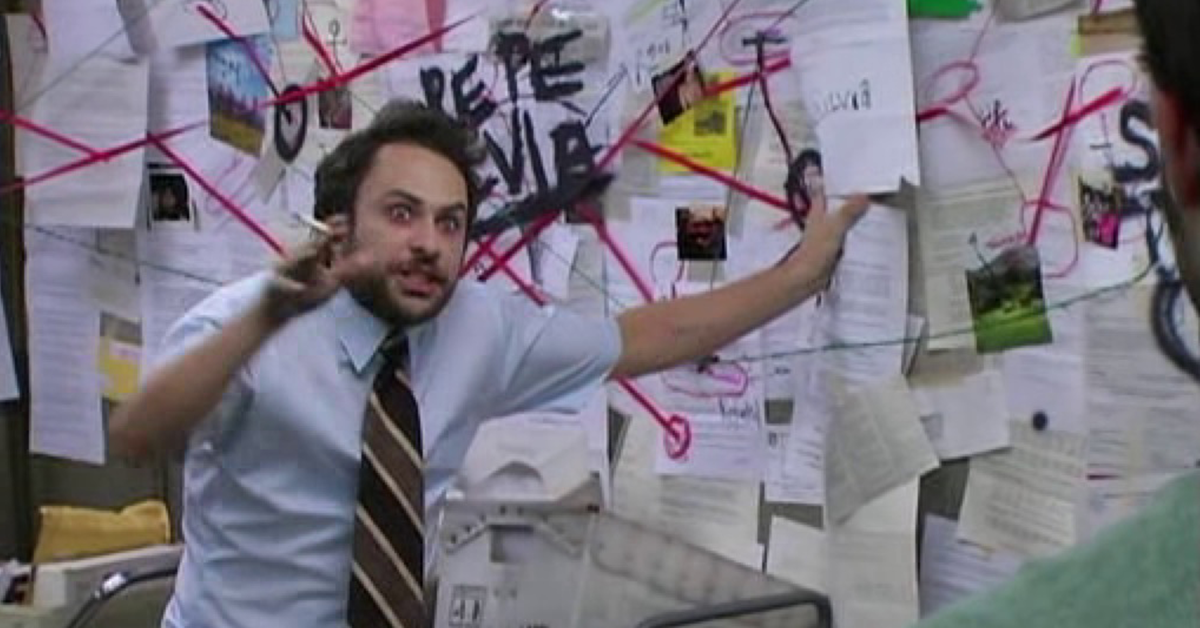

When I create a ficton, I start with what I know and try to figure out what else I’m going to need to know to actually run a game set in that ficton. At first these things are obvious: if you’re running a fantasy game, you need to know how magic works; if you’re running a Fast & The Furious game, you need rules for car chases and stunts; and if you’re running a Guy Ritchie game you’re going to need to come up with a bunch of character names that are simultaneously dumb as hell and cool as shit. As you start pinning things down, each new thing you know about the world will introduce a whole new set of questions. As things get more detailed, you’ll have to start making value judgements about which of these new questions need to be answered before you can run the game. Just because something exists in the game world doesn’t mean you have to know how it works. Focus on the things you’re going to have to know to running the game. Overdesign is bad. It also wastes time that could be used focusing on the important stuff.

In Cinemechanix, I break the idea of a ficton down into five core elements: Setting, Genre Trappings, Dramatic Rules, Tone and Mood, and Influences. Since that particular order of elements puts the most central and easily-recognizable aspects first, it works well for describing what a ficton is or presenting a finished ficton to an audience. However, all of those elements are interrelated actual design is a lot messier, so you’ll probably be jumping from one the other a lot as you try to pin down what your ficton’s all about. Trying to describe that would lead to a messy series of blog posts, though, so I’m going to go with an order that seems like it will work for talking about design (and hope it works): Influences, Setting, Genre Trappings, Tone and Mood, and finally Dramatic Rules.

Since it’s short, let’s go ahead and get influences out of the way. Every story borrows from those that have come before it, and admitting where you’re stealing from is a great way to help make sure everyone’s on the same page. Influences are often a handy shorthand to describe other elements of the ficton. For example, the group might decide that they want magic that works like it does in the Harry Potter books, fight scenes like a John Woo movie, or spaceships that look like the ones in Firefly. Citing influences can be especially helpful when discussing tone and mood. If you’re playing a game about killer sharks, establishing whether it’s influenced more by JAWS or Sharknado goes a long way in making sure everyone knows what to expect.

If I had to describe Guardians of Shymeria in mash-up form, I’d probably go with “He-Man meets Ralph Bakshi’s Wizards.” Those are the two central influences, but 80s fantasy animation and art in general are going to influence the design process. I’ll also probably borrow from non-animated fantasy fiction, especially pulp-era fantasy like Conan and trashy 80s fantasy movies. Since there’s an ancient ruined civilization right in the middle of the map, there will probably be some nods to Gamma World and various post-apocalypse stories as well. The war between Good and Evil that’s brewing can’t help but be influenced by Tolkien and Star Wars. If you made a soundtrack CD for the game and put it in a jewel case, cover art by Frank Frazetta would spontaneously appear.

Next week I’ll talk about the setting.